The Criminal Defense Lawyer in Fiction by Ralph Shamas

The defense of a citizen in a serious criminal case—when the charge is, for example, capital murder—is too overwhelming for a great many lawyers. In point of fact, most law school graduates deliberately maneuver to get an offer from a civil or corporate law firm. The notion of battling the government in court for a client whose freedom or literal life is at stake is often suppressed in favor of the more relaxed task of arguing the meaning of a contract or the question of whether or not the stop light was red or green. And more often than not, success in a civil practice is generally more profitable than the same measure of success for a criminal lawyer.

The natural question is why any law school graduate would pass on a less demanding, more profitable career in civil or corporate law and instead turn to the rigors of criminal defense. Well, the answer is that there are those individuals who want more than eight-to-five days and a big salary. I submit, respectfully, that you might understand this better if you follow the lawyer, Bruce Sanah, in his quest for justice in my novel, The Homicide Chronicle: Defending the Citizen Accused. Lawyer Sanah will lead you through the many emotions and challenges which a criminal defense lawyer must confront during a capital murder trial. Sitting next to a man or woman in court, knowing that if you lose, your client will die from lethal injection or sudden electrocution, leaves a lawyer with a sense that he or she must be the best possible advocate for the client. There is no room for anything less. And no doubt, the lawyer occasionally must rise to this level even in the face of incriminating evidence and unexpected developments at trial. Bruce Sanah will show all of this to you.

In a perfect world, the lawyer would always know when the client is innocent. Well, it just does not happen that way. The Homicide Chronicle

Of course, there are cases when it is absolutely clear that the client did commit the crime charged. Those are the easy cases. The lawyer will then do what he or she can to obtain a plea bargain, or raise a valid defense such as insanity. But more often than not, it is not so clear. The client will claim innocence and the evidence to the contrary will just not be that conclusive—an eyewitness without a clear view or whose identification was tainted by a suggestive lineup; questionable scientific evidence; a jailhouse snitch looking for a favor from the government. There are countless scenarios where that question of guilt or innocence must be decided somehow. The lawyer’s job is to present the client’s case in its best light and then let the jury decide.

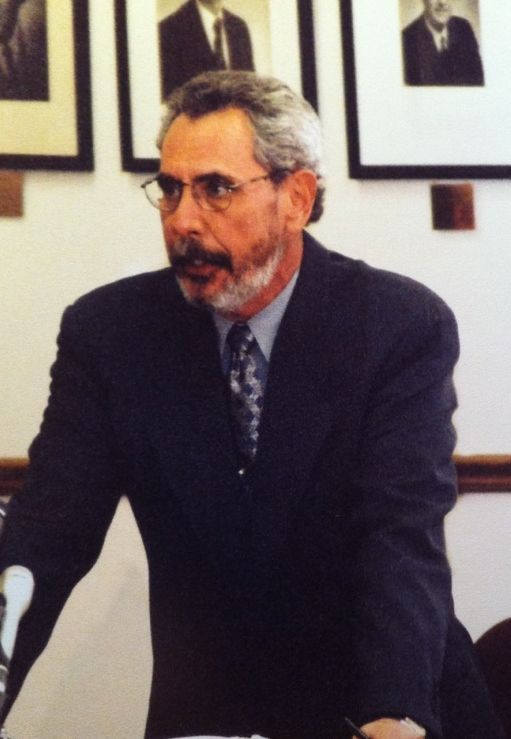

There are a great many misconceptions about criminal defense lawyers, and multitudes of people who are critical of the work the defense lawyer must do. During the years I practiced law, I lived with those misconceptions and criticisms. I have always tried to explain the justice system to others, but it always seemed to come off a bit empty somehow. Then after I was appointed District Judge, watching criminal defense lawyers struggling to be their best for their clients under difficult and sometimes impossible circumstances, it came to me—I would present the real truth in fictionalized cases. My reasoning was that the only way to really ask others to understand is to have them feel like they are actually there—defending the citizen accused.

Just like many of you, I read as much of the legal fiction as I can get my hands on. I love to read the novels of John Grisham and Scott Turow, for example, and I would never presume to compare myself with them. They are wonderful and creative authors, skilled at presenting sensational and dramatized stories. My objectives, however, are a bit different. My stories are fiction, but the cases, the evidence and the characters, come from trials I have actually experienced. I want you to enjoy the fascinations of the American justice system, but I also want you, as a reader, to see how the unpredictable twists and turns of a criminal case actually impact the criminal defense lawyer and how the lawyer must stand strong in the face of all conflict and adversity.

I thus believe that the compelling responsibilities of the criminal defense lawyer, and the coincident mysteries of the law and jury trials, are best presented through real cases, fictionalized to protect the people who were actually involved. My objective as a writer is to take the reader through it all from behind-the-scenes, living day in and day out with the defense lawyer as it really is. If you read any of my work and come to better understand our judicial system, as well as to be chilled by the real facts of murder and crime, then I will have succeeded as an author.

Best wishes,

Ralph Shamas

Ralph Shamas